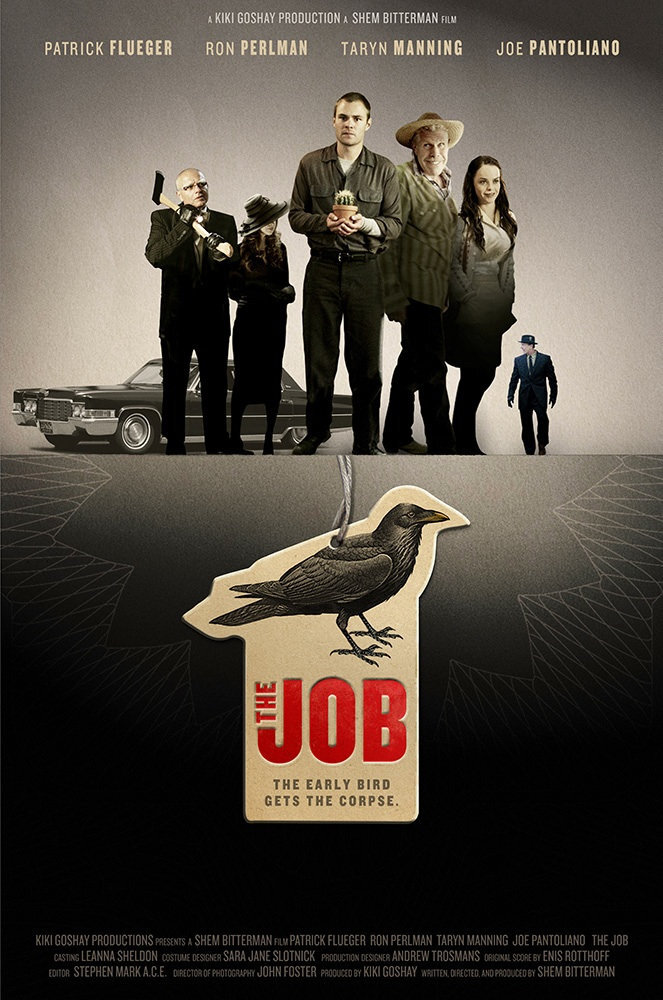

The Job

I was hanging out at a Downtown coffee shop in 2008 during my first Spring in Detroit when I met Shem Bitterman, a screenwriter from LA crewing up to shoot an independent film. I told him that I was credentialed in such things, having secured a BA in Media Arts from Wayne State University. I showed him the cheesy “City Kids” music video I’d made three years prior. He told me to meet him in his office the next day, and to bring my resume.

That night, I wrote a resume.

Shem knew I was inexperienced, so he offered an unpaid production assistant position. Everyone knows that people in Hollywood are honest, so I shook his hand on the verbal agreement that I wouldn’t fuck his production by being a fool, and we got to work.

“The Job” was perhaps the first or second film to take advantage of Michigan’s new film incentives, a state program that refunded 42% of production expenses back to films shot in Michigan, which had so few people qualified to do this work that another film in production at the same time had already gobbled up the qualified crew, and the United Auto Workers didn’t seem to have any script supervisors at the ready. Over the next five weeks, I was a PA on set and in the office, I joined the locations department and learned that job, the cast and crew expanded from around a dozen to over one hundred, and we made a film.

This was still the era before social media’s takeover, before smartphones were common, and when Detroit was continuing to slide rapidly into ruin, which would climax five years later when the city went through bankruptcy. The city streets were empty and the Downtown buildings largely shuttered and distressed, and there was a sense that humanity has simply gotten up and left some time ago. It was a ready-made film set.

The locations manager was from Chicago and the location scout had been fired, so Lizzy Zagoreos and I became “locations assistants,” learning the management job and providing our local knowledge to the out-of-towners. Once shooting began, I was charged with creating a daily document to be distributed to the cast and crew showing a map of that day’s location in relation to base camp, hotels and hospitals, with turn-by-turn driving instructions on the bottom half of the page and a hand-drawn map on the top. I could look at Google maps and draw, but I couldn’t simply print them out. This is how I memorized the complex street plan of Downtown Detroit, and it layed down a foundational skill that I later used to run my tour business.

I got to choose some locations, and suggested filming in Detroit’s Masonic Temple, the world’s largest, with three theaters, multiple ballrooms, a radio station tower and over one thousand opulent rooms. After a private tour of the complex, agreements were signed and the art department got to work. All of that for an office scene involving Joey Pantoliano grumbling under some thick fake old-man eyebrows while intimidating the protagonist.

I have a cameo. Composer Enis Rothoff wrote music for a fictitious rock band, so I assembled one comprised of the band I used to record, Chinese Happy, augmented by me on accordion, crewmember Ben Dresser on guitar, Keith Bedore on bass, Jay Fielder on drums, Mike Fiedler on guitar and contact juggler Flec Mindscape on crystal balls. We all appear on screen for just a few seconds.

Working on this production became my film school education. The Hollywood system, with its militaristic hierarchy of jobs, aggressive timelines and high stakes was a welcome shock to my creative sensibilities, having always worked in a more holistic way. One of the crew griped that working on this movie was taxing because of its low budget, and it twisted my mind, because millions of dollars were being spent and I had been accustomed to having to ask to borrow a video camera for free when I had wanted to make my films. Even when I was in University, the department had been so underfunded that there weren’t enough DV cameras for the number of students, and it was sometimes simply not possible to shoot an assigned video. But this crew member was upset because the giant table full of free food didn’t have fresh orange juice? Apparently having some budget is different than having no budget at all.

When production wrapped, the filmmakers told me I had been essential, and in a surprise gesture, paid me. Then I was invited to LA to participate in postproduction. I flew out, sat in on the 5.1 sound mix with the director and composer in Burbank, took photos for the motion graphics in the title sequence, helped proofread the closing credits and joined the above-the-line crew in the first, silent screenings of each color-corrected reel of film at a special screening theatre at Universal Studios (after which I joined a crewmember in sneaking around the unattended set of “Desparate Houswives")

The next year, I returned to California for the film’s premiere at the San Diego film festival, where it won the award for best screenplay. I stole the movie poster from the event, and Shem signed it: “You shook the hand!”

A few years later, Michigan’s film incentives were cancelled and Hollywood vanished, like the Road Runner zipping off and leaving behind a little cloud in the shape of a road runner.

In 2019, my partner and I went to LA and visited Shem and his family. We hung out all day, had brunch and got ice cream.